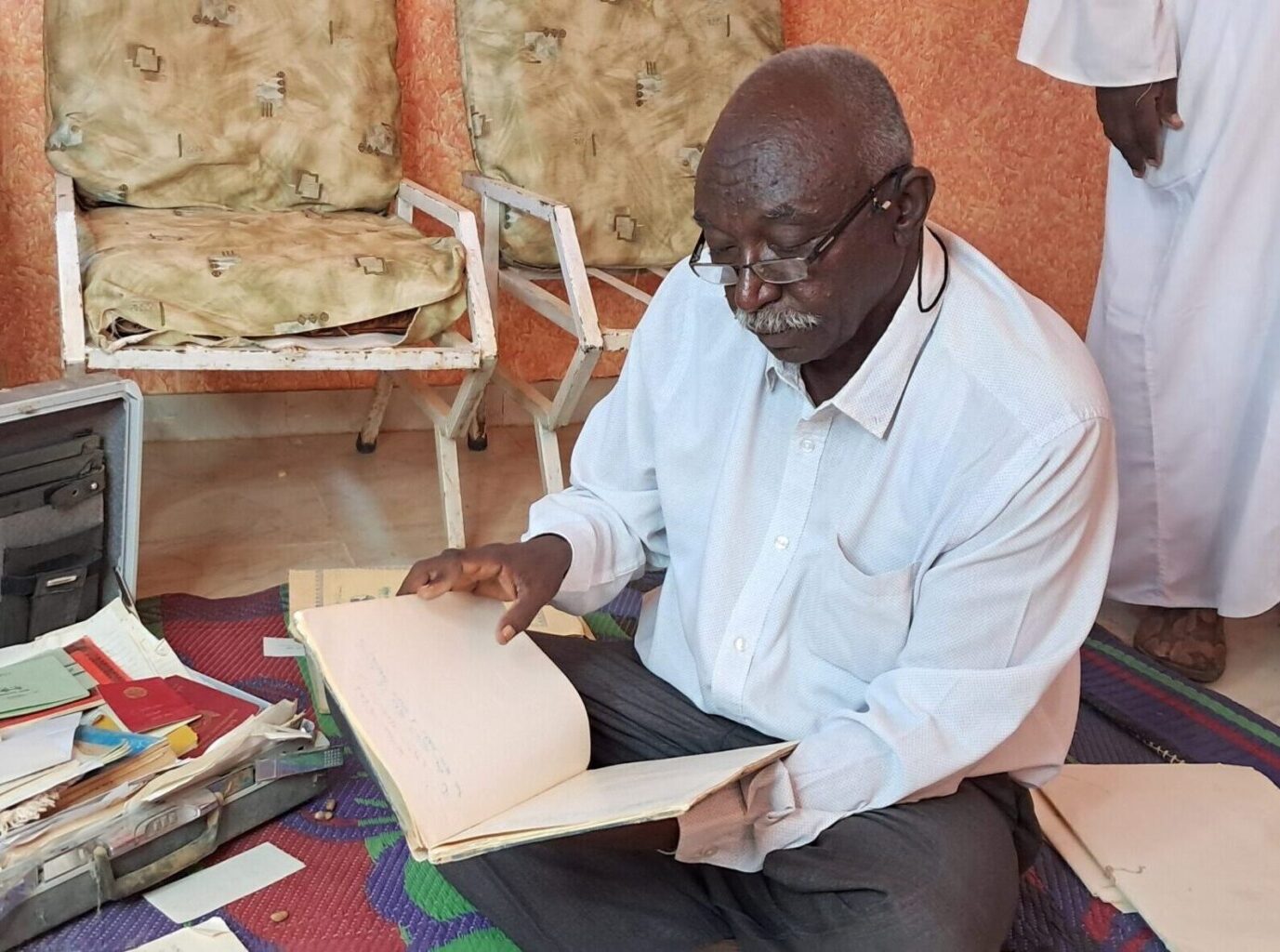

Merowe locality nudges up against the Nile River in Sudan’s Northern State, close to the hydroelectric dam and more than 300km north of the capital city, Khartoum. When Wahbi Abdalrahman and his team from Nile Valley University (NVU) arrive here with their Epson and Canon scanners, their laptop and digital cameras, the outside temperature is often pushing towards forty degrees Celsius. The area has changed in the last couple of years since the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) were repelled from Merowe soon after the start of Sudan’s civil war in April 2023. The traditional Wednesday market is still bustling, but many of the goods being sold are now Egyptian, rather than Sudanese, and customers include huge numbers of displaced people who have escaped the conflict that rages elsewhere in the country.

Against this challenging backdrop, Wahbi’s team sets up its travelling digitization unit. Since April 2023, funded by two six-month Cultural Emergency Response grants secured with Professor Marilyn Deegan, they have scanned more than 60,000 pages of documents in Sudan’s Northern and River Nile States. Many of these documents are from family collections. Still, they constitute and record important events in Sudan’s history that were either always absent from official narratives during Omar al-Bashir’s dictatorship or are now being erased by the ongoing civil war.

Using their digital camera and audio-recording equipment, Wahbi’s team has also captured video footage documenting accounts of abandoned markets, forgotten historical figures, and traditional practices in the region. He always travels with a notebook. In this he records any stories or extra details told to him by the collection owners about the items being digitized because, over the years, his team has come to appreciate that each belonging is more than an image, it has a story. Preserving these stories and historical traces will be crucial for understanding and remembering this period.

Sudan has one of the richest, most diverse heritages in the world with 19 major ethnic groups. In just over a decade, Sudan Memory have digitised more than 400,000 items

Sudan Memory digitization project

Wahbi’s work contributes to the broader Sudan Memory (SM) project initiated in 2013 to digitise cultural heritage at risk of decay and destruction in Sudan from climate change or possible future conflicts, the scale of which has far exceeded what was imagined at that time. NVU is one of several Sudanese and international partners contributing to the project, that also includes Sudan’s National Records Office (NRO), The Sudanese Society for Archiving Knowledge (SUDAAK), the Women’s Museum of Darfur, the Sudan Radio and Television Corporation (SRTC), University of Khartoum, University of Durham, and King’s College London, amongst others.

Sudan has one of the richest, most diverse heritages in the world with 19 major ethnic groups that speak over one hundred languages and dialects. Its archaeological heritage reaches back several millennia, and the country has more than 200 pyramids, as well as being rich in funerary goods and remains, wall paintings, and artefacts, about which most of the world beyond Sudan is ignorant. In just over a decade—and despite a coup, regime change, and conflicts—SM partners have digitized more than 400,000 of these Sudanese cultural heritage items.

During the project, the partners uncovered unexpected riches, such as the original copy of a telegram sent by Zubair Pasha from Cairo in 1883, hidden inside a manuscript in a village north of Berber, and original letters handwritten by the Mahdi, all of which Wahbi and his team carefully digitised. The growing digital collection now comprises films, photographs, manuscripts, museum objects, audio files, oral histories, and even a 3D, interactive, historic model of Suakin Island, as well as all associated Arabic and English metadata. What all of these items attest to is a rich and resilient culture that is stronger for its long history of diversity and co-existence.

To erase any record of the diversity and cultural co-existence is a tried and tested weapon of war worldwide

Conflict and culturcide

Attempting to erase any record of such cultural co-existence is a tried and tested weapon of war worldwide. In recent years, we have witnessed the Taliban dynamite the Bamiyan Buddha statues, the Islamic State destroy the temples at Palmyra, and the deliberate burning of the Sarajevo library, an event that Bosnian theatre director Gradimir Gojer described as, “a triumph of barbarism and the death of the cohabitation of Muslims, Orthodox, Catholics and Jews that had existed for centuries in Bosnia-Herzegovina.” As spaces for “shared memories and identities” when such monuments, archives, museums, and libraries are erased in conflicts, they leave behind only what SOAS professor Dina Matar describes as memory “gaps” (Matar, 2023, cited in Khaled et al. ,2023).

Since April 2023, we have seen these kinds of gaps emerge across Sudan, threatening to puncture its memory. In Khartoum, as elsewhere, RSF forces looted, damaged, or destroyed thousands of precious artefacts at the National Museum that documented Sudan’s long history and culture and the many civilisations that occupied this region over the centuries. UNESCO has warned of a “threat to culture”. At the same time, Ikhlas Abdel Latif Ahmed, director of museums at Sudan’s National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM)—one of SM’s founding partners—stated more emphatically that RSF forces “destroyed our identity, and our history” (Copnall, 2025).

The Sudan Memory collection is now all that remains of large parts of Sudanese culture; so many physical artefacts, collections, and buildings have been destroyed since 2023

Reports and anecdotes from SM partners and acquaintances still in Sudan describe the destruction of the Sudan Radio and Television Corporation buildings, previously one of the most extensive film archives in Africa with radio, video and film recordings that date back to the 1940s and provide a unique historical resource for Sudan. We understand that partners in other parts of the country have certainly lost collections, and as the full extent of the conflict is revealed, we anticipate news of many more memory gaps.

In South Darfur state, in the town of Nyala, the collection of over 4000 items, which was collected and curated for the Darfur Women’s Museum to tell the many different stories of the region, has been rescued and placed in a secret location. However, under current circumstances, it is not possible to display these items. As Kate Ashley, SM Consultant Project Manager, noted, this collection, “really demonstrated how just personal, everyday collections and objects can be put together and understood in this way that really sort of documents the social history of a place and has so much meaning.” Currently, only the digital collection that SM spent months photographing in 2021—along with a beautiful interview with the museum’s founder, Fatima Mohamed Al Hassan, sadly now deceased—is all that is currently accessible, and only through the SM website.

Archival sanctuary

We know that the Sudan Memory collection is now all that remains of large parts of Sudanese culture since so many physical artefacts, collections, and buildings have been destroyed since 2023. The project has, of course, taken on a new urgency against this backdrop, both in terms of ensuring the long-term survival of the existing digital artefacts and facilitating the digitization of other heritage records that are threatened with loss.

That Wahbi and his NVU team can continue their work with very limited assistance from outside Sudan is a testament to the SM project’s decentralised approach to digitization. In the early days of SM, project leaders Dr Badreldin Elhag Musa (SUDAAK) and Professor Marilyn Deegan (King’s College London) envisaged conducting all digitization activities at a central hub in Khartoum’s Africa City for Technology. In 2017, however, at the first project meeting after securing grants from the British Council and Aliph Foundation for £800K to initiate SM, Sudanese partners made it clear that they instead wanted scanning activities to take place on location, in decentralised hubs. Intense negotiations ensued, but the funders agreed to support this.

Memory gaps must be addressed so that people can rebuild their culture and their stories with dignity and hope

One of the many positive outcomes from this decision is that digitisation skills have become embedded in these partner institutions. Individuals trained by the SM—such as Wahbi—were empowered to train their colleagues and develop their own digitization teams, enabling work to continue even now.

Partner institutions, like NVU, also kept the equipment provided during the project and made decisions about which materials they would digitise. Of course, like all institutions, entrenched bureaucracy and power politics influenced which materials were selected for digitization. In some cases, items that the SM team deemed valuable, but the holding institution considered too controversial—or reputationally sensitive—were not selected for digitization. On the other hand, Sudanese partners, like Wahbi, who have an intimate understanding of how culturally sensitive certain topics are for Sudanese society, were able to make careful assessments about whether private collections—like those held by families in the Merowe locality—should, in fact, be made public.

This approach to selection and appraisal was essential in building trust with Sudanese partners who were understandably suspicious about being exploited by the kind of extractive digitization projects experienced elsewhere on the African continent. In these cases, Africans had committed their labour and cultural heritage resources to digitization projects funded by institutions in the Global North only to find they had no access to, or control over, the digital artefacts they had produced (Breckenridge, 2014; Pickover, 2014; Rassool, 2018; Chamelot, Hiribarren, and Rodet, 2020).

In a concerted effort to mitigate these concerns about neocolonialism, the SM project is based on a series of agreements and memoranda of understanding that ensure partner institutions maintain ultimate control over how the digitised items are reused, as well as keeping digital copies of the items. So, while archival-quality digital copies of thousands of SM items are stored in the King’s College London research data repository (KORDS), permission to reuse any of the digital items first requires contacting the original rights owner. Tragically, the ongoing conflict means many of these rights owners are now missing, some presumed dead.

In the immediate post-conflict period, the digital collection will be an important resource for remembering and revitalising Sudan’s shared, diverse identity and its rich heritage

In other cases, where Sudanese partners did not give permission for digitized copies of materials to leave the country, these have also been destroyed along with the tangible versions, so that nothing remains other than a gap. Yet, as Ikram Madani, Head of the Natural History Museum, University of Khartoum, notes, “If our physical collections have been destroyed as a result of the war, then at least we will have the digital records of items to rebuild our collections from.”

Post-conflict

The SM project’s intention has always been to return the digital repository to a Sudanese institution and to keep another version as a copy somewhere outside the country. In the immediate post-conflict period, the SM digital collection will be an important resource for remembering and revitalising Sudan’s shared, diverse identity and its rich heritage, important building blocks for negotiating a future based on cultural coexistence for which there are, undoubtedly, clear precedents. In a recent oral history project conducted by Sara El-Nager, where she interviewed participants about their roles and reflections on the SM project, many noted the positive personal impact the project had on them. They spoke effusively about travelling to other, less familiar parts of Sudan, where they met people from different walks of life, which showed them the cultural diversity of Sudan but also what many had in common.

How these resources are deployed will be determined by Sudanese communities both within the country and its growing diaspora. For Asia Mahmoud, an SM Local Coordinator and Collection Researcher, this digitization project is about so much more than its content:“A lot of people actually faced this shock of losing everything [ during the war], and it became personal to everyone. Projects like SM not only preserve our history, culture, and heritage, it will actually be like a solace for everyone; it feels like we’re here, we still exist.”

Making sure that the digital resource is available post-conflict depends, however, on ensuring that SM in its entirety receives sanctuary somewhere that safeguards and preserves against the threats of corruption, degradation, and obsolescence in the long term. The urgency of this is incomparable with the need to alleviate the suffering currently being inflicted on Sudan’s people and to secure an end to the conflict. Our wish is, however, that by guaranteeing the long-term future of SM, it can address the memory gaps so that people can reconstruct their culture and histories with dignity and hope, and in ways that safeguard peace agreements.

Bibliographic references:

Breckenridge, Keith. 2014. “The Politics of the Parallel Archive: Digital Imperialism and the Future of Record-Keeping in the Age of Digital Reproduction.” Journal of Southern African Studies 40 (3): 499–519.

Chamelot, Fabienne, Vincent Hiribarren, &Marie Rodet. 2020. “Archives, the Digital Turn, and Governance in Africa.” History in Africa 47: 101–18.

Copnall, James. 2025. “From Prized Artworks to Bullet Shells: How War Devastated Sudan’s Museums.” BBC News, April 26.

Khaled, Mai, Heba Saleh, Lucy Rodgers, Alexandra Heal, & Dan Clark. 2023. “How the Loss of Entire Families Is Ravaging the Social Fabric of Gaza.” Financial Times, December 13, 2023.

Pickover, Michele. 2014. “Patrimony, Power and Politics: Selecting, Constructing and Preserving Digital Heritage Content in South Africa and Africa.” Paper presented at IFLA WLIC 2014 – Libraries, Citizens, Societies: Confluence for Knowledge, Lyon, France, August 16–22.

Rassool, Ciraj. 2018. “Digitisation and the Government of Collections.” Paper presented at Postcolonial Digital Connections, Halle, Germany, May 16-17.

Photography

Man reviewing archival documents by hand, surrounded by folders and papers, during the process of digitizing historical materials. Author: Wahbi Abdalrahman (Sudan Memory).