Four women, mothers or sisters of disappeared persons, bear witness to their tireless struggle to find their loved ones again and to the impact, at a personal and collective level, of facing up to a disappearance. On the basis of their own experiences, they reflect on the need to clarify the truth of each case and to do justice as a means of reparation and non-repetition.Voices from Algeria, Colombia, Mexico and Honduras.

1. When and in what context did the disappearance of your relative take place?

Nassera Dutour, founder of the Coalition of Families of the Disappeared in Algeria (CFDA)

My son Amine was 21 years old. He was arrested on 30 January 1997 and he has been missing since then. He was at home that day and went out to see a friend. When they were together they realised they didn’t have their papers on them and they both returned home, because at that time in Algeria the police could stop you to demand your documents at any time. Amine went out again and a white car wasthere. Theymade him get in and he disappeared. They were probably agents of the intelligence service, but anyway we never heard from him again. Since then I have been struggling to discover the truth. In my search I met other mothers who were in the same situation as me and in 1999 we decided to create the Coalition of Families of the Disappeared in Algeria (CFDA).

Gladys Ávila, spokesperson for the European Group of Relatives of the Disappeared in Colombia

My brother Eduardo Ávila was arrested and disappeared on 20 April 1993, in the context of the Colombian armed conflict. He was 26 years old and I was 29. He had been a member of the M-19 guerrilla organisation, but they demobilised in 1990. We found his body a week after his disappearance, on a highway outside Bogotá. We recognised him by visual identification, because the police hid the data and closed the case for lack of evidence, without there being a possibility of DNA testing. Eduardo had the letter T, for his nickname Tiger, tattooed on his left arm. It was a tough moment. I could see the torture: his tongue was torn, his jaw was broken, he had wounds on his hands and fingers, and several gunshots. We managed to get the body handed over to us and since then I have been fighting for justice to be done. In a case of enforced disappearance, it’s just as painful to keep searching as to find the body.

Yolanda Morán, director of the organization BÚSCAME and member of the Movement for Our Disappeared in Mexico

My son, Dan Jeremeel, was kidnapped on 19 December 2008 by a group of military personnel from the intelligence area. He has been missing since then. Eleven years later the case is still open: no progress has ever been made in the investigation because the case involved the military. We believe that it was a matter of misfortune: he was in the wrong place at the worst possible time. A few days after the kidnapping, four people were arrested: a military officer, in possession of my son’s car, and three accomplices. They were found guilty and sentenced to prison. When they were in jail, two armed truck drivers entered the prison and killed them. That put an end to any possibility of finding out more about the facts. There were still two fugitives at large, one of whom was detained and then also killed. Apparently nothing is known about the other one. Since then, the family has been dealing with the investigation, pressuring the authorities. A mother does anything to find her child.

Edita Maldonado, member of the Committee of Relatives of Disappeared Migrants from El Progreso (COFAMIPRO), Honduras

It was in 1995. My eldest daughter left home headed for the United States in the hope of helping the family. She was 28 years old. She stopped in Chiapas because she couldn’t continue the journey. I went five years without hearing anything from her, because her letters didn’t arrive. It wasn’t until 2000 that the postman delivered one of her letters to me and I managed to find her. The migration route to the United States, not only from Honduras, but also from El Salvador, Guatemala… is a horrendous odyssey, a terrible ordeal for people who go out looking for a future for their families. Migrants are victims of organised crime in Mexico: there are kidnappings, imprisonments, deaths…

2. What is the impact of a disappearance at a personal and collective level?

Nassera Dutour

The disappearance of a loved one is the most tragic and shocking thing that can happen to a parent. If your child dies due to natural causes, the suffering is unbearable, but over time the wounds may heal. When it’s a question of an enforced disappearance, that healing never comes, the wounds are always open. The family lives between hope and despair. The hope of seeing the child alive again, the despair of the years that go by, and the fear of never seeing them again. It’s a constant pain that burns inside and never goes away. There’s also a sense of feeling guilty because you weren’t able to protect them. Disappearance is a torture that deforms you and stops you living a normal life.

Gladys Ávila

My life changed completely. I was a fashion designer, looking after two children and a home. Following that 20 April, I was unable to rest because I knew that I had to go out and look for my brother, to search the streets, shelters and hospitals, from morning to night. You search among the living and the dead. A disappearance destroys your family life and your social life. The family wants to find out who is to blame, to know what happened and why. In our case, as a result of what happened, the family discovered that my brother had been a member of M-19 and this had such a strong impact that the family unit broke up. At the same time, we are stigmatised, labelled and blamed within society. A disappearance is a risk to life and a stigma for the family; that is why it’s so important to know the truth.

Yolanda Morán

It’s a huge mental, emotional and psychological impact because we cannot get rid of this constant pain. When a family member dies, you say goodbye and you have a place you can go to mourn them, but we have no such place. We don’t know if our children are alive; we don’t know where they are or how they are. Every day, when I sit down to eat, I ask myself: “Will my son have a plate of food? “What condition is he in?” This uncertainty is the cruelest thing that can happen to a human being and their family. Dan Jeremeel has five children; the youngest was two years old when he was kidnapped. His wife is alone, without the father, having to go out to work every day. It’s a terrible trauma that generates anxiety and doesn’t allow you to live in peace.

Edita Maldonado

A disappearance means the destruction of the family, it means despair. For five years I dreamt of her every night, without knowing where she was. It’s a very difficult situation for many families, and that is why we came together. Since we formed the Committee of Relatives of Disappeared Migrants from El Progreso (COFAMIPRO) in 1999, there have been 680 disappearances on the migration route between Honduras and Mexico. We organized the first mothers’ caravans, and asked the Honduran government for help in creating a search commission, but they never took any notice of us. The government has tried to silence the protests and has only helped us with the repatriation of migrants’ bodies, but it doesn’t recognise the disappearances.

3. What positive factors can you point to from the tireless struggle of the families of disappeared persons?

Nassera Dutour

The families organise ourselves to demand justice, we go out onto the street every week, we organise events, meetings, protests, with banners and photographs of our sons and daughters. We mothers are forced to keep struggling to discover the truth. The pain is stronger than we are, and the anger, the rage, the sadness, and also the hope, all these drive us to fight and to keep going. It is mainly a struggle by women, because we are stronger than men, because we don’t give up trying to find our children, although we must also remember that many mothers, and also fathers, have died over this time and others have fallen ill.

Thanks to our struggle we have managed to keep the cases of our children open, despite the Algerian authorities having declared them closed, and the UN Human Rights Committee has recognised 6,146 disappearances in Algeria at the hands of state officials.

Gladys Ávila

When my brother was disappeared, I came across the Association of Families of the Detained-Disappeared (ASFADDES). They accompanied me in the search and thanks to them we found the body. I continued with the group, supporting the many other searches, first as a volunteer and later as the coordinator of the association. Each individual victory is a victory for everyone. From there we fight to survive, we educate ourselves as women –because it’s practically a movement of women– we manage to organise ourselves and we get a political education.

I have continued the struggle from exile. In 2006 I was expelled from my country due to the disappearance of a member of our association. My life and my family’s lives were in danger, and I was exiled to Sweden. That was another very difficult moment due to the added difficulty that it entailed, but we have managed to form a European Group of Families of the Disappeared in Colombia, present in ten countries, and we work with the Unit for the Search for People Considered to have Disappeared in Colombia. Feeling that it’s worth fighting, facing up to everything, that I didn’t nullify myself as a person; that’s the most positive thing.

Yolanda Morán

Through our pain we have found friends. One year after the disappearance of my son, while I was on my way to the public prosecutor’s office, I met two other mothers in the same situation and we joined together to form FUUNDEC (United Forces for Our Disappeared in Coahuila), the first organization of relatives of the disappeared in Coahuila. We went from 18 families, in the beginning, to 600. We started growing, we gained legislative experience, we learned about our rights and, in 2019, we decided to launch BÚSCAME, a new organization. Now we focus on the work of identifying bodies and exhuming mass graves, and we are part of the Movement for Our Disappeared.

We have seen a change of course with the López Obrador government, the first administration to recognize the problem and provide information on the number of disappeared persons (around 61,000, even if from the organizations of relatives the number is estimated to be 200,000). We are working with the government and have made progress in the implementation of the Law on Enforced Disappearances, passed in 2017. If there is something a mother doesn’t do, it’s abandon her children, and this is our fight. It is sad to have met one another under these circumstances, but together we have learned to be strong and not to be afraid of the authorities. Although we receive threats, we leave our fear at home and keep on fighting. Unity strengthens us on this road full of obstacles.

Edita Maldonado

The most valuable thing is our courage to keep fighting, to keep going, to help the mothers who haven’t found their children. I was lucky to find my daughter, I brought her back to Honduras but she got ill and died in 2004. Even so, I stayed in the Committee to accompany the others, because we are all one family. We mothers are the bravest and those who struggle most. Hope gives us the strength to fight.

4. What do justice and reparation mean to you?

Nassera Dutour

Reparation is for justice to be done and to know the truth. Without justice there can be no reparation. We need to know what happened, where our children are, whether they are alive or dead, who arrested them and why, what they had done to be arrested, why they didn’t have the right to defend themselves, why those responsible haven’t been prosecuted… we must know all these things. Why didn’t they tell us the truth at the time? If they are dead, why didn’t they return the bodies for us to bury them? If no one gives us answers we can’t close the case and we cannot forgive. And for our inner peace we have to be able to close the case.

Gladys Ávila

Knowing the truth, for the country to be able to recognise what happened. Reparation is the public recognition of the identity of the disappeared person, it means non-stigmatisation. And, for justice to be done, the aggressor must explain what happened, who is responsible and why, so that it doesn’t happen again. Society must understand that enforced disappearance is a problem for everyone. It was a social genocide and society must put itself at the centre of the struggle. According to the figures published in Colombia, there are between 80,000 and 120,000 missing persons, but there are thousands more unreported cases. The country is not prepared to face up to the disappearances, some people are afraid of the truth being made public, but we always maintain our hope and one day we will have the light that allows us to know what happened.

Yolanda Morán

Before demanding justice for ourselves, the main purpose is to find our children. Bring my son home; find him, give him back to me. That’s the first thing; that’s inalienable. I live to find him, regardless of what condition he is in. I will think about justice later on. Of course I want those responsible to pay and that is why the authorities are obliged to keep on investigating, but I am so full of pain that there is no room for hatred or rancor in my body. The damage has already been done. We keep on fighting, pushing our way forward; we help one another to find them all. Our faith in God sustains us.

Edita Maldonado

Reparation comes from knowing the truth of what has happened in all these disappearances. Those who ordered the killings of migrants are to blame for the disappearances. We demand justice for all, we want the truth.

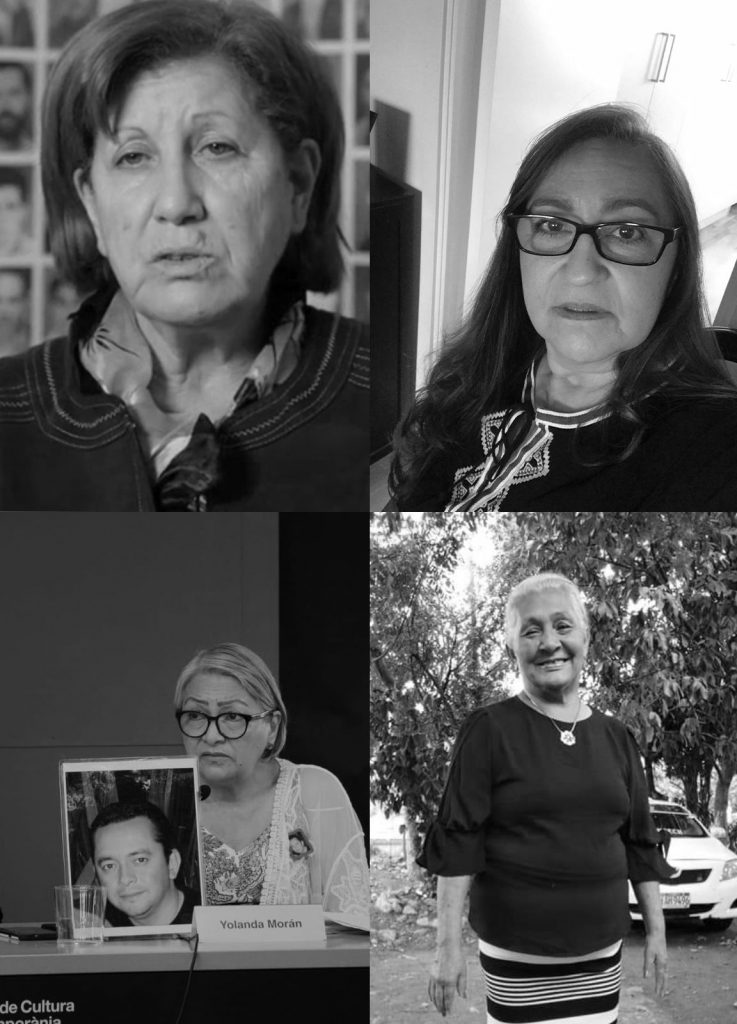

Fotografia From left to right and top to bottom, Nassera Dutour, Gladys Ávila, Yolanda Morán and Edita Maldonado.

© Generalitat de Catalunya