To mark the 25th anniversary of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda (UNSCR 1325), ICIP and the Escola de Cultura de Pau (School for a Culture of Peace) held the event “Where Are Peace and Security? Feminist Proposals” on 12 November at Pati Manning. The session set out to analyse progress under this international framework and, above all, to reflect on its challenges in a global context shaped by war, rearmament, and authoritarian pushback.

The opening remarks were delivered by María Villellas (Escola de Cultura de Pau) and Kristian Herbolzheimer (ICIP), who situated the discussion in a political moment that is especially hostile to women’s rights and to the defence of multilateralism.

The programme featured a keynote lecture by Sarah Taylor, an expert on gender, peace and security policies, followed by a feminist conversation with Carmen Magallón, Nour Salameh and Patricia Simón, moderated by Pamela Urrutia.

Successes, limits and a “captured” agenda

In her keynote, Taylor reminded the audience that Resolution 1325 is the result of decades of activism by women in conflict contexts and that it has helped generate more inclusive international frameworks and peace processes.

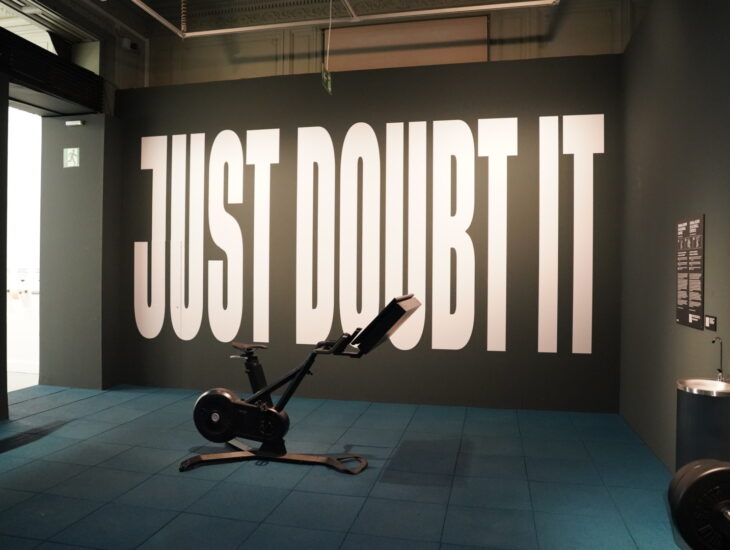

Yet she sounded the alarm about a structural problem: the political capture of the agenda. As Taylor explained, once institutionalised in bodies such as the UN Security Council, the 1325 agenda became conditioned by the interests of states, especially permanent members, who prioritise their geopolitical and military objectives. This shift weakened its antimilitarist core: the original spirit of questioning militarism and the logic of war has progressively faded because it clashes directly with the priorities of the most powerful states in the international system.

This capture is also reflected in the lack of accountability in conflicts such as Gaza, Sudan or Myanmar; in the shrinking funding for feminist organisations; in the persistent confusion between “women” and “gender”; and in the limited attention given to LGBTQIA+ communities.

According to Taylor, reversing this trend requires putting grassroots peacebuilders and community organisations back at the centre, with consistent political and financial support, in order to recover the transformative potential of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda.

A feminist conversation to defend life and democracy

The roundtable, featuring Carmen Magallón, Nour Salameh and Patricia Simón and moderated by Pamela Urrutia, delved into the current implications of militarism and violence.

Carmen Magallón, Honorary President of WILPF Spain, described the present moment as “very hard and very dark times”. She stressed the need to protect Resolution 1325 as part of international law and to reclaim the basic concepts now under attack, starting with the notion of humanity. Both Magallón and Simón also warned of the importance of countering far-right narratives that target and attract segments of young men, and of promoting proposals that uphold equality, coexistence and democracy.

Researcher and ICIP Board member Nour Salameh brought the discussion to Syria. She argued that feminist peace is grounded in the living memory of women who have resisted decades of war and authoritarianism. She criticised how the WPS Agenda has often been instrumentalised — inviting women to negotiation tables without transforming the patriarchal and militarised structures that shape those processes.

Journalist and ecofeminist Patricia Simón denounced what she described as a “declared war” against those who produce critical thought (feminists, pacifists, journalists), in an attempt to erode democracy and impose an order based on hatred. She highlighted the strength of the global solidarity movement with Palestine and the active participation of young people. And she reminded the audience that while international humanitarian law is being openly violated, it is precisely the “utopian radicals” who are defending norms and the rule of law

An agenda that must continue to be defended

The session made it clear that, despite the political instrumentalisation that Resolution 1325 has suffered, the transformative power of the WPS Agenda remains alive in feminist solidarity, in the demilitarisation of public narratives, and in the active resistance of grassroots movements and communities working for peace.

Far from giving it up, the speakers agreed that this is precisely the moment to deepen the agenda and to reclaim its original anti-militarist spirit.