Talking about education for peace in contexts where violence s intense or has direct repercussions raises questions not only for peace education, but for the very conception of peace, as well as for those who work for peace. For that reason, different responses and options can arise which aim to open spaces of peace, making it possible to start breaking the cycles of violence. In the words of the researcher John Paul Lederach: “peace is seen not merely as a stage in time or a condition. It is a dynamic social construct. Such a conceptualisation requires a process of building”1.

In areas with forms of direct violence it is essential to make visible, open up and sustain this peace-building process, as a first step in the reduction of violence. It is important to convey the idea that despite the violence that is being or has been experienced, there is a way of acting such that violence does not continue to be the answer to what is happening or has happened. And it is through the actions for peace that spaces are created which bring fresh air and make it possible to reduce its intensity. Some of these peace actions consist in responding to questions such as the following. Who are we? Who are we with? Then, following the idea of resilience: What is it that we do have? What is it that we can do? And finally: What are we already doing in peace actions?

To gradually interweave such actions within the various spaces, the creation of a peace network helps. This network allows us to move away from the position of indifference, paralysis and normalisation created by violence, as well as to obtain new perspectives and tools and, above all, when violence reaps its toll, to generate spaces for care and healing.

Peacebuilding in Mexico

To talk about Mexico today is to show a broad mosaic with many tonalities, in which elements of profound darkness are combined with others of brightness and great hope. It is to see that life goes on, and that life takes care of life. It is important to show aspects of peace that are being worked on in Mexico such as the creation of peace networks, in rural hamlets, in the communities, peace spaces and practices in official schools, restorative practices in prisons, among others, which are sometimes not made visible in the face of the strong impacts left by violence. This violence is not fixed in one place, but movable, and has a varying intensity, with momentary peaks. But, precisely, these peaks are intense, accentuated, and provoke fear among the people. Therefore, it is important that spaces of peace exist that can gradually transform what needs to be shifted and transformed.

To talk about Mexico today is to show a broad mosaic with many tonalities, in which elements of profound darkness are combined with others of brightness and great hope

To speak of Mexico is to show its diverse realities, as well as those of the world. The point is that the violence here has a lot to do with the violence there, so achieving peace here is linked to achieving peace there. It is to see that we are interdependent, we are interconnected. And it means having a broader vision and a more open heart. Since we are all interwoven and the privileges of some are the violence of others, let’s see how we can begin to take care of each other and see ourselves as a shared, connected and interdependent humanity.

Peace proposals and practices

In the light of these reflections and of the conception of the pedagogue José Tuvilla who creates peace spaces in schools, here are a series of proposals that could be applied in Mexico to promote a culture of peace in schools, through good practices that Francisco Muñoz defines as “spaces which offer equilibrium, safety and sustainability, all of which are very important conditions for peace; we can see that there are many spaces of ‘imperfect’ peace at the micro, meso and macro levels of human societies”2.

It is therefore about creating spaces for meeting, dialogue, caring, recognition, active participation and networking. This is where peace is built.

Connection spaces

It is highly revolutionary to return to the connection of the human being with him or herself, with the other and with nature, to make the pauses necessary to see what is alive in me, in the other and to take care of life. One of the methodologies that allows this is Marshall Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communication (NVC), which recovers the connection, observation, feelings and needs in the face of a conflict, situation or event so as to formulate a petition.

Spaces for meeting and cooperation

The educational community has different spaces for coming together, which can be spaces for meeting and building relationships with people. One way is through cooperative games, as a way of finding ourselves through caring, collaborative working and changing our mindset from competitiveness to cooperation. Activities in which you can see the need for a paradigm shift from the individual to the collective, from just one group to the collective in general, where it is not just about broadening our thoughts but also our heart.

Spaces for recovery, curing and compassion

When there has been direct violence, it is important to offer spaces where the cycles of violence are broken. When a person who has been a victim of violence does not have an adequate space for recovery or curing, the pain they have suffered can easily provoke a new cycle of violence in which this person becomes the perpetrator of violence. Many perpetrators were previously victims. That is why offering spaces for recovery, reconciliation, forgiveness or healing is important in being able to rebuild despite the violence that has been experienced. The necessary tools include exercises in mindfulness, the creation of circles of peace and exercises in compassion.

Spaces for networking

John Paul Lederach suggests that to establish platforms of transformation it is necessary to weave networks. The creation of these networks has to be with people who are close, not with people who we want to change or convince or who we think need it; and there has to be a primary network held together by everybody and other complementary networks can emerge from there. These networks are sustained through activities, meetings, sharing experience or giving support or help in situations of conflict or crisis.

You have to create spaces for meeting, dialogue, care, recognition, active participation and networking. This is where peace is built

These spaces for peace are established through different practices of peace:

1. Practices of peace from the human: one would think that it is not necessary to educate human beings to be human, but what violence does is precisely to disconnect the human being from themselves, from life and from others. That is why the capacity to reconnect the different dimensions of the human being within everyday practices will make it possible to break the cycles of violence and enable a peace-building process.

Through activities that promote the recovery of the capacity of amazement, enjoyment, connection, caring for oneself and for others.

2. Dignifying teaching work. If we are saying that recognition is one of the first spaces of peace, it is important to include teaching work within that recognition, dignifying the work that is already being done, and at the same time generating a collective educational conscience, as well as favouring the creation of bonds of union between the different groups with their own diversities and styles for the good of the collective.

The intention of practices of peace is for them to multiply themselves within the school communities themselves through the peace networks and for these to offer alternatives, even in situations of crisis.

Experience of Peace Education

In this context, it is worth briefly presenting a concrete experience of peace education that was carried out from 2017 to 2019 in high-risk regions of the State of Mexico: the diploma in “Holistic Peace and Coexistence in School” offered by Integrated Educational Services to the State of Mexico.

The face-to-face phase of this diploma was carried out in areas of Valle de Toluca and Valle de México where there are high rates of violence. Eight groups of 40 teachers participated, most of them professionals working in the field of education in high-risk areas and who have sometimes been the direct victims of violent acts. Through the construction of a network, many schools were involved in the project.

The experiences of peace in Mexico are diverse, but little publicised. Bringing them together through peace networks makes it easier to see their impact and importance

In addition to creating this network of peace educators, the Diploma was an important space for reflection that revealed some key issues and challenges for peace education in Mexico. Among them, we can highlight the following points: Educators who work in areas of high violence often have a negative conception of peace, thinking that it is only the absence of war, but also at the same time a romantic idea of peace, in the sense that things have to be perfect to achieve it and that we are all going to love each other and hold hands. That is why one of the first actions is to present peace in the plural, that is, as “peaces”: different forms with which one can work, a wider, more tangible and practical vision of the concept of peace. At the same time a peace of the here and now, the idea that as we are imperfect we can establish an imperfect peace which is an ongoing process, even in areas where there is violence. In violent settings, peace is conceived as something distant, so it is important to bring it closer, to live it as a space that makes it possible to break a cycle of violence. The idea of holistic peace that was proposed in contexts of violence was a peace with me, with other people, with other realities. This requires the use of different dimensions of human beings’ ways of learning: bodily, emotional, intellectual and life experience. Understanding holistic peace as the sum of the parts plus the whole, where each action –whether internal or external– affects the whole.

In areas where violence is present, and more so if it is continuous, the darker aspects of humanity become normalised and have an impact on us. This cycle of violence is not only external, but also internal: it disconnects you from life, from yourself and from other people, with more violence being generated by despair. That is why it is important to generate hope through the recognition of the actions that they do carry out in their own setting, with what they do have and can count on, especially focused on their students and what they can do together. In addition, for people who work in violent places, it is important that they also have their own spaces for recovery, for connecting with life, as well as for recognition of their work and self-recognition.

A proposal that helped in violent areas was establishing peace networks, among teachers, school management, families and students, as such a network allows them to fulfil their need to be heard, understood and motivated to be peace builders in their educational community. And to see that there are several of us who are building options to restore equilibrium in what is happening.

Peace in Mexico has changed from an ideal to a space of proposals from which some concrete actions have already emerged

Experiencing violence at first hand, rather than just attending to or working with people who suffer violence, increases its effects on us. Often it paralyses us. Therefore, in terms of peace, we must understand the possibility of the process, make visible what is happening, name it and also point out the peace actions that already exist. We must identify what we can do, without putting our own physical safety at risk, since many times students come from families where not only is there domestic violence, but also where other forms of violence are exercised. In these cases, what a teacher can do is to work on peace with the students who come to the school, opening a space of encounter with others, on the basis of nonviolent communication, cooperation, resilience, where each person’s environment determines the attitude. In the face of so many spaces of risk, we must generate more spaces of protection.

Conclusion

The concept of peace is something alive, that moves, that allows dialogue between life and what is not life. It is not an ideal, it is the continuous construction of humanity, the space, the practice that humanises the human and where we meet each other as humanity.

The possibility of generating spaces and practices of peace in places where violence is experienced is not only real and important, it is a necessary step and we have to make known the tools that make these practices possible. Even with the challenge of there being very few specialists, there are more places being created every day for training in issues of peace, such as peace circles, restorative circles and practices, nonviolent communication or cooperative peace games. It must also be borne in mind that more and more universities are establishing postgraduate courses on issues related to peace education and culture.

There is still a long way to go, but it must be acknowledged that, over the last five years, peace in Mexico has changed from an ideal to a space of proposals from which some concrete actions have already emerged.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gloria María Abarca Obregón has a doctorate in International Peace, Conflict and Development Studies from the UNESCO Chair of Philosophy for Peace at the Jaume I University of Castellón. Coordinator of international peace education projects and of the DEEP peace network. Winner jointly with Said Bahajin of the City of Castellón Peace Prize for 2009. She is also a researcher and teacher on the subject of holistic peace education in various States of Mexico, Colombia, Paraguay and Spain.

1. Lederach, J. P. (1997), Building peace: sustainable reconciliation in divided societies. United States Institute of Peace, Washington DC.

2. López Martínez, Mario and Francisco A. Muñoz (2004), “Historia de la paz” in Molina Rueda, Beatriz and Francisco A. Muñoz (eds.), Manual de Paz y Conflictos, Granada, University of Granada, pp44-65.

This is a translated version of the article originally published in Spanish.

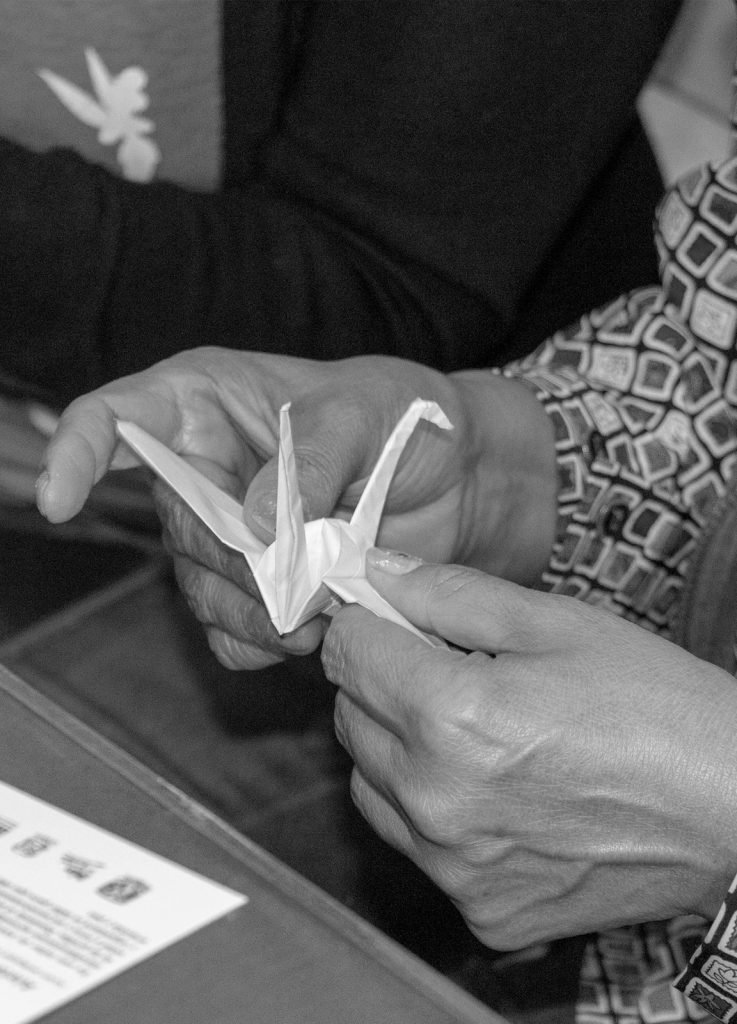

Photography Documentary meeting for peace

© Generalitat de Catalunya