The aim of this text is to give recognition to the role of Mexican young people in the peace reconstruction processes that are necessary and urgent in Mexico. The levels of violence that are currently being reached have serious effects on young people’s experience of daily life. The fear and the terror being sown, the distrust in institutions and the despair generated by governments lead to a situation where being young is a risk factor which brings no privileges but, at the same time, is a status full of possibilities of resistance.

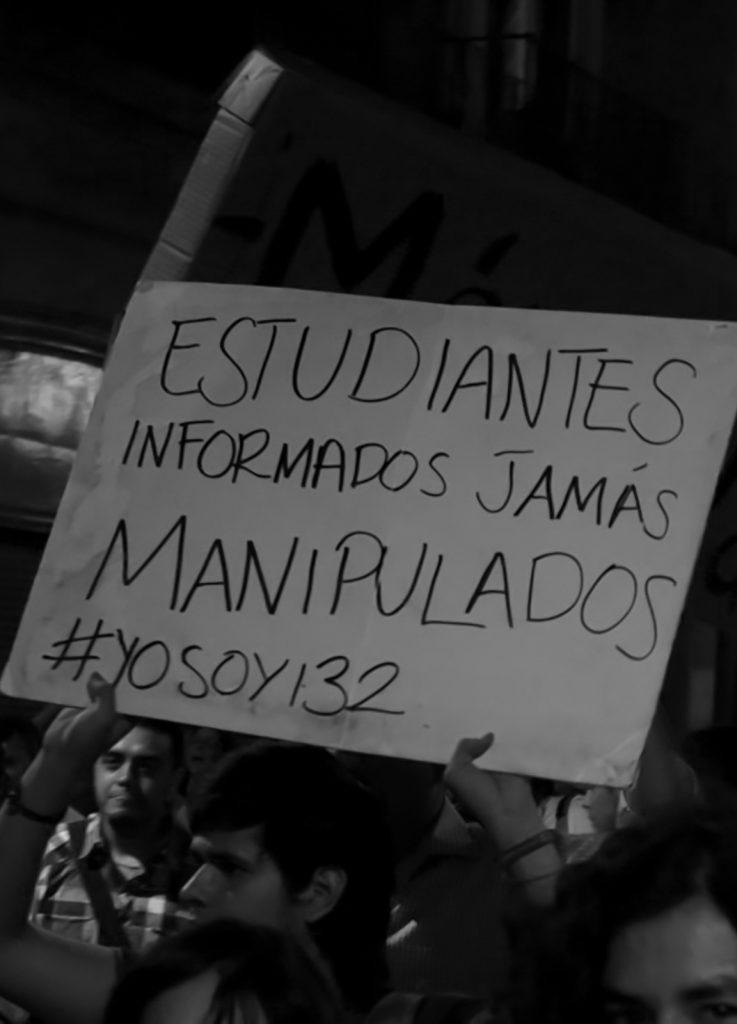

Today’s Mexico cannot be separated from two events which are fundamental to understanding the self-organisation and mobilisation of Mexican youth over recent years. The first is the disappearance of 43 teaching students in Ayotzinapa, in the state of Guerrero in 2014. This event unleashed a collective discontent that sharpened the rejection of the government of the time. It should be mentioned, however, that before that government had taken office, another movement had emerged, #YoSoy132, in opposition to the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto. #YoSoy132 called for the democratisation of the media, the economy and education. The exasperation was already there and, when the state’s involvement in the disappearance of the 43 students came to light, there was outrage at a level that had not been seen for many years.

As those who disappeared were students, there was a very significant element of identification created so that, from this moment on, we young people began to experience a type of consciousness that we had not felt before. The pain experienced in 1968 with the Tlatelolco massacre was revived in Mexican people’s collective consciousness and student mobilisations began. The fact of being a student once again became a risk factor. This was confirmed in 2018 with a second significant event: the forced disappearance of three film students in the city of Guadalajara. The young men were making a video as part of their professional training when they were captured by members of a drug cartel. The official story or “historical truth” of the Jalisco Prosecutor’s Office is that they were killed and disposed of in sulphuric acid. However, the ambiguity in the evidence and the lack of precision in the details of the investigation meant that the anger and discontent with the state increased.

How can we care for each other in a country where human dignity, safety and freedom are not a priority?

In the cases of the 43 Ayotzinapa teaching students and the three film students, one factor that accelerated the publicising of the cases was that the families and friends of those affected went into action immediately to make the facts known and to demand justice. As a result of the upset generated by the events related to the students’ forced disappearance, young people’s relationship networks went into action, generating endless strategies to express the rage felt in the face of the structural violence that was clearly implicated in the events. On the other hand, young people’s self organisation led to a rethink about what we can do to put caring at the centre of things: that is, how can we care for each other in a country where human dignity, safety and freedom are not a priority?

These events produced a breach of normal daily life in universities, on the streets and in social networks. Within the universities there were active stoppages, assemblies, meetings to discuss collective actions. In the streets, many symbolic acts, marches and slogans expressed this discontent in the public arena. Social networks were full of information about the case, of “missing” posters, and debates and discussions took place about the events. Undoubtedly, the families have been the most affected and those most involved in these processes, but the role of young people is crucial in understanding how these movements of indignation have been sustained. It should also be noted that universities, streets and social networks are privileged spaces, such that the most mobilised sectors are also those that are most privileged.

Gradually the involvement in political issues spreads in response to the growth in the number of people affected by such events. The increase in violence and the disproportionate fear with which we are living are becoming a general question, to the point that although many things continue to be silenced and the privileges of a few are preserved, there are dialogues being opened today that in other circumstances would perhaps not occur. The sensations of terror, discontent, disappointment and frustration have brought us to name and make visible our shared needs.

Given the scenario of violence in which we find ourselves, we have gone from indifference to indignation. It is well known that more and more people are implicating themselves in the political and economic situation of the country. It is no longer so common to hear expressions like “I’m not interested in politics” which we often used to hear when we were children. As we have grown up, we have come to realise how dangerous that indifference was, in a country that requires us to use all the instruments, actions, reflections and resistance that we have within our reach.

Given the scenario of violence in which we find ourselves, we have gone from indifference to indignation

In the same way that we face the forced disappearance of thousands of young people in the country, over recent years feminicidal violence has increased massively, coming to affect especially the lives of young women. The murder of Lesvy Berlin at UNAM, the best known university in the country, unleashed indignation and rage, leading to the mobilisation of many women’s networks. The slogan #NiUnaMenos (Not One Less), which had already been raised by Argentinean women, became the symbol of an urgent and essential demand in Mexico. It has contributed to making visible the institutional failure in the face of the tremendous wave of feminicides where not even universities and other well known places are safe spaces. Lesvy’s case is one of the thousands that occur in our country. Nowadays, new cases of feminicide are recorded every day, so this the state of alert is a call on us to mobilise.

It is important to talk about the women’s movements over recent years since feminism has come to be seen in different ways and with new meanings in the common sense of Mexican women. Feminism used to be a bad word, tinged with radicalism or exaggeration, while today we see 13-year-old girls defining themselves as feminists with the conviction that they themselves must defend their rights. From the emergence of the debate on the decriminalisation and legalisation of abortion, the reflections concerning the right to decide about our bodies have become a watershed in identifying the possibilities of defending ourselves. In many cases, self organisation and mutual support among women has been the answer. A few years ago, in feminist marches and meeting spaces we almost always saw the same faces. Recently, the need to question the absolute truths that we have been taught culturally has become part of critical and self-critical processes.

It is clear that feminist discourse and practices permeate the lives of young women. We see how in all the universities and beyond them, feminist groups, seminars, meetings, etc. are being organised. And there are more and more demands for protocols on dealing with gender violence, as well as more demand for training courses for teachers in issues related to gender perspectives and for specialised materials on the subject, something that before seemed a distant dream for Mexican female university students. We see women’s meetings organised by the Zapatista comrades, by autonomous spaces, by collectives and spaces of ongoing political education among women of all ages. These actions promoted by the different feminisms generate care practices that are clearly different from the hegemonic and paternalistic discourses regarding safety and care. Feminist resistances are characterised by putting politicisation, sisterhood and emotions at the centre, which clearly have to do with the reconstruction of peace. Feminist care strategies are key to the rearticulation of the Mexican community, since feminisms have taught us about the meanings and the power of protecting dignity and equality as guiding principles of our actions.

One of the great contributions of youth for a less violent Mexico has been our questioning of the power relations we were taught us see as natural

Over recent years, these networks have produced new forms of protesting and organising to demand and insist on a decent life. The objective is not to seek answers and solutions provided by the state, but to occupy and take over spaces and build new ways of connecting ourselves and living our lives. The strikes and active stoppages of #8M are an example of this. International Women’s Day (8 March) has been redefined by feminist movements, not as a celebration that reproduces patriarchal practices and discourses, but rather with a political content, as a reminder of the historical debt that society owes to women.

The typical images associated with youth have generated the belief that this is a stage characterised by indifference about what is happening around them, in which concerns are focussed on social life, having fun and not taking responsibility for one’s own life and for social, collective issues. However, the current situation has led young people to grow in the face of the adversities and dangers, thus favouring the development of critical thinking from an earlier age. Thus, Mexican young people are very much in contact with the needs of a country overrun by violence and in which strategies must be sought to organise resistance.

Universities remain important locations for organising in the face of violence. On other fronts there are also actions by autonomous spaces, young indigenous people who continue struggles that began with uprisings by their grandparents, young people who join groups of mothers looking for their missing sons and daughters, alternatives to the parties with political proposals articulated by young people, as well as the political use of media and social networks. Multiple possibilities open up of critical spaces aimed at reflection and organisation around diverse themes: gender violence, collective care on the basis of self-management, the increasingly widespread gentrification processes in Mexican cities, forced disappearances, urban mobility, environmental crisis; that is to say, a range of issues that are constantly interlinked. The arts, journalism, research, audiovisual productions, the use of big data and geolocation tools are some of the elements of interdisciplinary collaborative knowledge that are being put at the service of the community with the aim of achieving a better city and a better country for everyone. They are a substantial part of the construction of the historical memory of all these collective actions.

The construction of peace in Mexico must start from the most everyday actions and from common sense, with caring, friendship, sisterhood and solidarity at the centre

Apart from the participation of students from the universities, from autonomous groups or from the professional tools that we young people use to resist in the face of violence, it is important to mention the value of self-criticism in our social relationships and our daily activities. It is recognised that one of the great contributions of youth for a less violent Mexico has been our questioning of the power relations we were taught us see as natural, putting into question heteronormative ideals or even questioning the meaning of our education, for example. These elements transform the interactions that make up our lives; for that reason, the exercise of self-criticism leads us to relationships more grounded in solidarity and mutual care. This critical attitude in daily life is changing the typical images concerning young people, making it possible to see them not as one single thing, but as a plurality of options where there is the possibility of encountering others in order to question, rethink, build and rebuild a more decent country for everyone.

We cannot ignore the fact that, to the extent that participation in organisational processes has increased, there has been an increasing polarisation of discourses in today’s conversations, producing tensions between the ways we identify ourselves. There seem to be no shades of grey in how we position ourselves over issues, either you are “on the right” or “on the left”, either you are “radical” or you are “soft”, leaving no room for the understanding of complex processes, leaving out all other factors to define something as black or white without allowing any other possibilities. Thus, when talking about a topic of common interest, it seems that there is a need to impose one viewpoint over others; it is a question of convincing rather than of building. We can note the existence of hate speech directed against those we identify with the other extreme, which is also something reflected in youth identities, in the struggles that are chosen and in the ways in which we position ourselves politically. The challenge we face is to be able to establish shared points of reference and feelings on the basis of the acceptance of difference. Despite the fact that the debates and reflections around common issues may involve disputed areas, we will have to find strategies to build together; otherwise, we will be losing one of the most important battles, making us unable to differentiate the nuances between the different tensions in which we are immersed as a society.

Regardless of the discourses that are in dispute, it is clear that there is a strong involvement of youth in the social development of our country. Questioning the decisions and actions of the state has become a daily matter, whether posting feelings and thoughts on Facebook or Twitter as a starting point for meeting and talking, or carrying out symbolic actions in the streets. It should be recognised that most of the organisational spaces are made up of and led by young people. It restores hope to think that in a few years it will be that group that will be capable of leading our country. Social movements, collective action and any type of organisational process; all these are crucial and open the possibility of a Mexico that is more critical, more sensitive and shows more solidarity, with the tools to rise up from the horror it now faces. It is essential to keep in mind that the construction of peace in Mexico must start from the most everyday actions and from common sense, with caring, friendship, sisterhood and solidarity at the centre.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

She graduated in Psychology at ITESO, Jesuit University of Guadalajara, Mexico. Her interests are collective processes, feminisms, gentrification and the relationship between technology and emotions. She has participated actively in various mobilisations in her city, in the feminist movements and in the interuniversity organisation against forced disappearances. She is part of the team of Signa_Lab ITESO, a laboratory for experimentation and research on networks.

This is a translated version of the article originally published in Spanish.

Photography #YoSoy132

© Generalitat de Catalunya