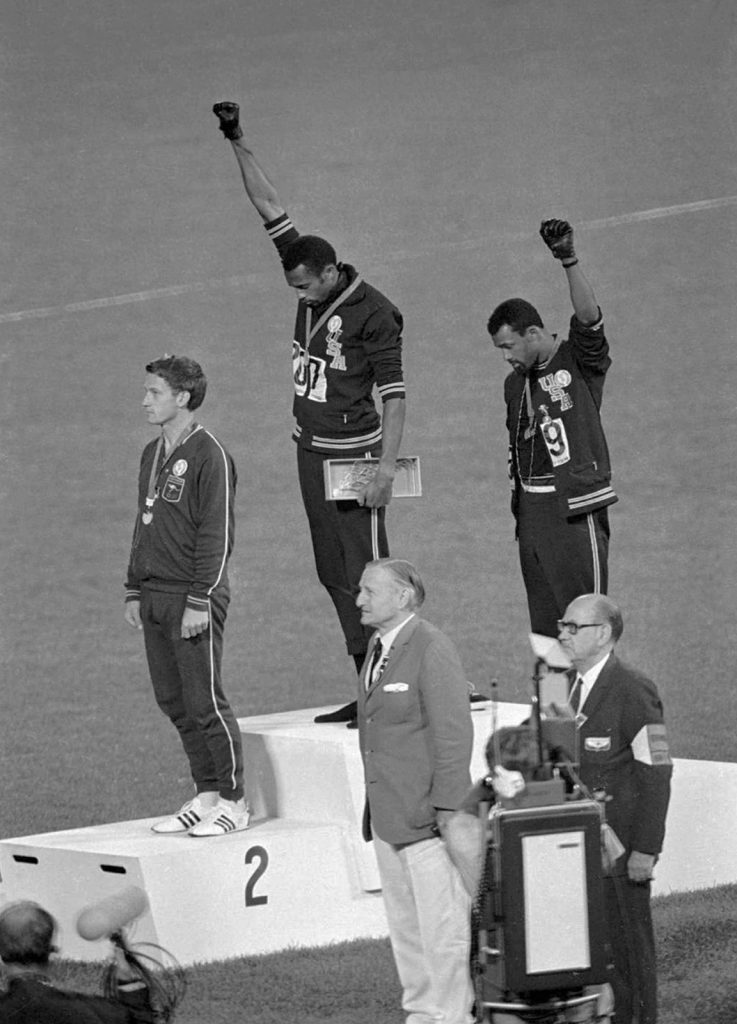

“Many friends treated us like heroes. But we had been expelled from the Olympic Village and my career was ruined. In the eyes of sports officials I was a traitor.” Tommie Smith recalled with some bitterness the day his name went down in history. Both he and John Carlos, standing on the podium of the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City, in 1968, raised their black-gloved fists while the US national anthem was played in their honor for winning the gold and bronze medals in the 200-meter race. “It wasn’t a gesture against the United States. It wasn’t a gesture against anyone. It was a gesture of black pride. If it was against anything, it was against racism,” argued Carlos. Both the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the US Olympic Committee, however, did not forgive this act of political interference in the Olympic Games, a supposedly sporting event. And two Olympic medalists were ostracized for having wanted to do their part in the fight against racism at a time when a fierce debate was raging over the subject in the United States.

The IOC, like the majority of organizations that control sporting events, claims that sport should not be used to talk about politics. But the Olympic movement was politicized very quickly by decision of the IOC. Even back in 1906, when the so-called Intercalated Games were held in Athens -an experiment that took place only once, and that aimed to allow the Greeks to organize intermediate games- athletes had no way of registering individually, but instead had to do so through National Olympic Committees. They were the first games in which a flag was raised to honor the winners. The games were no longer a competition between athletes but a competition between states. The Irishman Peter O’Connor, forced to compete for Britain, protested by climbing up the flagpole with an Irish flag, with the help of American athletes of Irish origin. Modern sport was born politicized.

Political demonstrations improvised by athletes in major sporting events have always been poorly received initially even though organizers have often used sports to send messages, as when Japan decided that the person in charge of lighting the Olympic flame in the Tokyo Games was to be Yoshinori Sakai, born on the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. An elegant way to send a pacifist message that was less controversial than the decision of American boxer Muhammad Ali to refuse to enlist in his country’s army during the Vietnam War. Ali, Olympic champion a few years prior, preferred to be sentenced to prison, fined and stripped of his passport for several years rather than participate in that war. He also lost his world championship title since he could not leave the country to defend it.

The gestures of O’Connor, Smith or Ali led to problems for the athletes, who were subsequently denied any kind of assistance to continue competing – and this, despite the fact that the Americans’ black fists have become one of the most famous images in Olympic history. In fact, the third athlete on the podium in those 1968 Mexico City Olympics, Australian Peter Norman, was also penalized by his federation because, upon learning of the two Americans’ intentions, he decided to support their protest by wearing a badge denouncing racism.

Many of the athletes who have decided to use sports to try to change the world have paid the consequences

In 2000, however, public pressure persuaded the organizers of the Sydney Olympics to use sport to try to atone for the sins committed against the Aboriginal community. It helped that athlete Cathy Freeman decided to run her victory lap with both the Aboriginal and Australian flags after winning a gold medal. Freeman, aware of her position of strength, used the media platform the Games offered to demand a gesture towards her people. “Australia has to look forward and, in doing so, it must heal its wounds. The country proudly celebrates my gold, but I want to be proud of being Australian and Aborigine at the same time,” she said. But Freeman had risked being penalized before when, in 1994, in one of her first successes, she celebrated her gold medal in the Commonwealth Games (a sporting event involving athletes from states that were mostly territories of the former British Empire) with an Aboriginal flag. At the time this symbol was not official, but the gesture influenced the debate that would lead to making the flag official under Prime Minister Paul Keating. Since then, however, Australian football players Adam Goodes and Lewis Jetta have had to endure racist insults, which have provoked their reaction in the form of celebrating successes with traditional indigenous dances.

Political and symbolic gestures in sports are increasingly more harshly dealt with, especially in football

If the fight against racism has been the focus of many protests for decades, in recent years many athletes have used sports to defend the rights of homosexuals, especially in handball, such as the Norwegians Gro Hammerseng and Katya Nyberg, who participated in the World Championship with their nails painted in the colors of the rainbow flag. The captain of the Swedish handball team, Tobias Karlsson, has played games wearing a rainbow flag bracelet even though it was forbidden to do so in this year’s European Championship in Poland.

Many of the athletes who have decided to use sports to try to change the world have paid the consequences. In 1936, German athlete Luz Long dared to give the US Afro-American Jesse Owens, his great rival in the long jump competition, advice to avoid being disqualified. Owens accepted the advice and beat Long, who had to settle for the silver medal. However, the German took it well, embracing the American and running the victory lap with him. A sporting gesture of great value since Hitler was in power in Berlin in 1936, and he did not approve of one of his athletes helping a black competitor. Long paid a dear price for it since, unlike other top-level athletes, he was sent to the front line when the war began and died in Sicily in 1943.

The election of the Russian city of Sochi to host the Winter Olympics in 2014 also encouraged several athletes to raise their voices against Russian anti-gay laws. Dutch snowboarder Cheryl Maas, for example, displayed a rainbow-colored glove just before participating in her event. The International Olympic Committee threatens athletes with heavy fines if they use sports to try to make political protests, especially after several cases of T-shirts used on podiums with messages relating to conflicts like those of Palestine or Kosovo, but Maas was able to avoid being penalized.

Political and symbolic gestures in sports are increasingly more harshly dealt with, especially in football, considered the most popular sport, and therefore a stage where historically protests of all kinds have been seen. Some, politically correct; others, not so much. From supporting workers on strike, like Liverpool’s Robbie Fowler, to the fight against homophobia, like Englishman Graeme Le Saux, who received homophobic insults even though he wasn’t gay. From demanding aid for war refugees to pacifist messages, football stadiums have been settings where players have gone beyond sports and have been, in many cases, fined. Being brave can often help to change the world. But it can also have negative effects on your career, as in the case of Tommie Smith in 1968, who went from breaking world records to working without a contract washing cars. Time, however, proved him right.

© Generalitat de Catalunya