In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf analyses the difficulties a woman faces in establishing a career as a writer; Woolf explains: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Decades later, and although regarding a very different context, something similar can be said of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, Women, Peace and Security. The resolution recognised the need to create this own room, at the international level, as well as within individual states and it has worked hard to collect several reports1 on this issue. However, as it currently stands, this room has not fully materialised, and it is not a room of one’s own, nor is it a space well integrated with the other spheres of international society. There are not enough funds to ensure that fifteen years from now we are commemorating a better situation.

In other words, the signs, fifteen years since Resolution 1325, are both encouraging, and disappointing; as expressed in the child’s school report card to the parents: “There have improvements and much progress, but we still need to see a lot of effort.” Effort has been made, but in order to have success there needs to be a slight change in approach. In the following paragraphs I will elaborate on this idea. The context since the signing of the resolution has changed; we therefore, must engage in a deeper reading of the text, and emphasise individually, both the overall meaning of the text and its four separate pillars: participation, protection, prevention and relief and recovery. We need to alter our approach, by applying distinctive perspectives and ensuring that we address, the root causes, the structural causes.

We begin by remembering key contextual questions. The UN’s founding agreement granted different responsibilities and attributes to its principle organs, including the Security Council, as outlined in the Charter. The Council has the primary responsibility of maintaining international peace and security, which is buttressed by many UN actions: Chapters V, VI, VII, VIII and XII of the Charter). In addition, Article 25 of the Charter establishes the obligations of Member States to fulfil their own resolutions. Resolution 1325 arose in the second decade of the post-Cold War era, in a context dominated by a concern for human security (harm done to individuals and communities), changes in the nature and location of armed conflicts; in a context of liberal-peace and discussions about humanitarian intervention and the responsibility to protect, particularly civilians and vulnerable groups. Concretely, the resolution mentions two other resolutions in 1999 (1261, 1256) and two in 2000 (1296, 1314), dedicated to the rights of the child, the situation of armed conflict and the protection of civilians, promoted by countries including Namibia, Netherlands, Bangladesh and Canada.

A full inclusion of women in efforts relating to human security constitutes a positive, necessary and essential contribution

The importance of resolution 1325 is therefore, significant, as is demonstrated in the conclusions to the international conference held in Washington, November 2010. Ten years after its adoption there were marked changes in approaches to issues of peace and security, notable changes in international law, the empowerment of women, in the planning and execution of military operations and in the conception of global security.

The best way to perceive these changes is to acknowledge how the resolution pays attention to these underlying questions, to regard its structure. By doing this, we notice that men and women experience security in different ways, and therefore, the exclusion or the insufficient inclusion of different perspectives has a negative impact. If one does not take into account these diversified approaches, made evident through a gendered base analysis, then we exclude the vision and the participation of women in processes related to peace and security. The result, as is demonstrated in several reports completed some years back, is clear: weakened negotiations and peace agreements, weakened strategies of reconstruction, peace building and development and weakened national economies. The inclusion of women’s perspectives and approaches, as well as their experiences and different priorities, shows greater sustainability in processes of peace building. We also have empirical evidence, based on specific cases of negative impacts (exclusion) and positive impacts (inclusion). Having one’s own room and money, according to Woolf, means success, although neither resources nor following a different approach have become fully realised anywhere.

We need a change in the approach on the four pillars of 1325: participation, protection, prevention and reconstruction

I therefore contend, that the principle conclusion to be drawn from Resolution 1325, fifteen years on, is that the active and full inclusion of women in efforts relating to human security constitutes a positive, necessary and essential contribution. To achieve this, the next fifteen years require a change in approach, one that focuses on two particular issues. First, there needs to be greater unity and coordinated efforts, between feminist movements and women and men peace movements, as with think tanks and national governments, none should evade the resolution, a resolution which puts emphasis on the different requirements of compliance for each country. Second, it is necessary to address the four separate areas of the constituting pillars: a) participation at all levels of decision making (local and intergovernmental); b) the protection of women, adult, child and adolescent, from sexual abuse and other violence, which is too common in wars, refugee camps and even in peacekeeping operations authorised by the United Nations (there must be plans to deal with trauma and other severe measures); c) prevention with a multilevel approach, (prevention of violent conduct, the persecution of violations of national law, strengthening the rights of women in national law and explicit support for the significant presence of women in peace processes and reconstruction); d) the adoption of measures to support humanitarian assistance and post-conflict reconstruction, which is crucial in a time where the humanitarian system is in a crisis worse than in 1945.

With that, I conclude by remembering Alva Myrdal and her work as a diplomat, a peace activist and a feminist (awarded the Nobel Peace Prize), we must not forget the profoundness of Resolution 1325: the urgency to address root causes and to delegitimise any approach that is not inclusive.

1. The most recent report, Preventing conflict, transforming justice, securing the Peace. A Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council resolution 1325, sponsored by UN Women and presented last October at the United Nations Security Council.

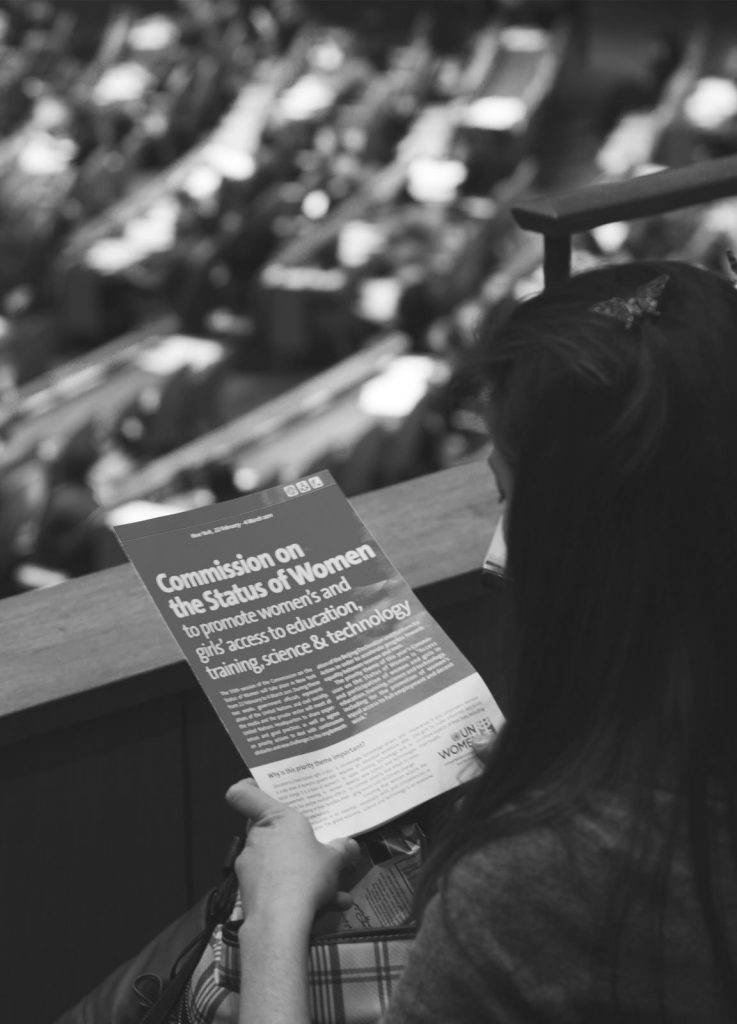

Fotografia : SustainUS

© Generalitat de Catalunya