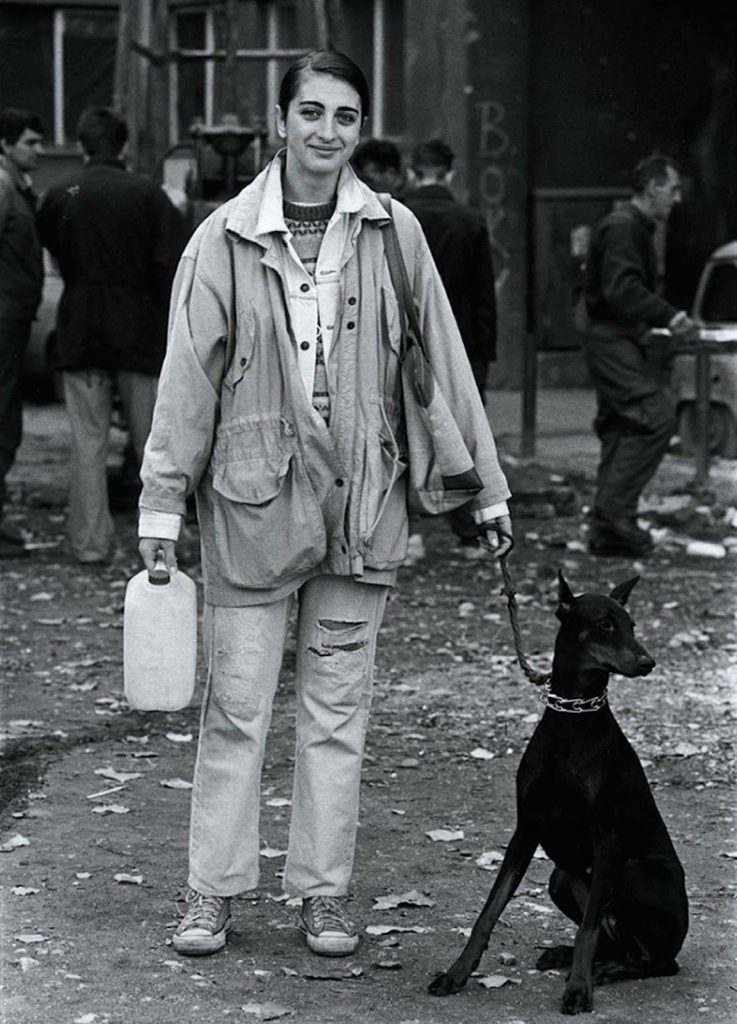

The first image that comes to mind when I think of women living under constant shelling in Sarajevo during its siege in 1992-95, is how well-dressed and dignified they looked. It was the first time I discussed with friends how being a feminist could also allow us into the use of stereotypes that mould women into cover-page models. In this case, being dressed-to-kill meant exactly the opposite of being violent: as civilians, under siege, without water, electricity and food, the only “weapon” of those women was to look their best. The only weapon was not being militant. The photo of Meliha Varešanović taken by Tom Stoddart in 1993, at the height of the siege and intensity of bombardment, is the best example of that image. She looks as if she has stepped down from a catwalk, gorgeous, fashionable and proud. She became an international media icon of the spirit and style of Sarajevo women defying war. Meliha recalls “In addition to the defiance reflected in that photograph, if you look a bit deeper, you can see sadness, because that year my mother died. It was a harrowing loss, an enormous pain and heaviness. I was on the verge of losing hope, but I remembered my mother saying that in life we always must walk with our heads held high, keep on going and be dignified.” 1 Looking respectable was important for many women. The directress of the Association for Culture and Art “CRVENA”, Danijela Dugandzic, remembers how when she and her late mother and sister left besieged Sarajevo they hardly had any money. Their mother used the money on latest fashion haircuts, which they showed off eating pizza in a European capital famous restaurant paying for it with the last remaining money.

Women always changed their underwear and clothes before going out to the streets of Sarajevo, because the constant bombing and shelling meant that there was such a high probability of getting bombed, injured or killed. “Being neat and tidy in case we ended up in the hospital emergency room”; taking care of that aspect of being presentable is almost unthinkable in all other life situations when women are about to step out of their homes.

“Women living in bombarded cities end up being heroes of peace, while men are esteemed for the battles they win”

Despite the majority of women who are not fighting on the frontlines, many women are killed by shelling and bombing of violent conflicts, which have had an increase of civilian deaths since the Second World War. The siege and shelling of Sarajevo also started with the death of two women, Suada Dilberovic and Olga Sucic, who were participating in the peace demonstrations against war in April 1992. They were killed on a bridge that is named after them today. Women living in bombarded cities end up being heroes of peace, while men are esteemed for the battles they win.

So many women living in shelled and bombarded cities are heard of only in the traditional role they have: as mothers, as pretty women, good looking and well dressed. U2 made a live video connection with besieged Sarajevo during one of their concerts and showed a Miss Sarajevo contest with the contestants carrying the sign “Don’t Let Them Kill Us.” These were all important images and messages, but then there were all those women working as doctors, nurses, as interpreters and politicians, trying to work in impossible conditions under bombardment and shelling who never made the news, and whose images never became the icon of a woman defying shelling in a besieged city.

Everyday life and taking care of a family under constant bombardment and shelling has probably earned women of besieged Sarajevo a degree in business and management and another one in being a magician. Cooking without electricity and scarce other heating resources was yet another burden. Finding food, and once found being able to pay for it, usually meant making meals out of nothing. Then having to prepare food meant using water, which was cut off and had to be hauled into the house in canisters, dragged in makeshift trollies, usually from far away. Water had to be brought for bathing, cooking, washing clothes. I have a friend who even to this day cannot bear to hear the sound of tap water flowing without being used. Another dear friend, Kika, now working on gender mainstreaming, gave birth to her son, during the war and she recalls how raising a baby without all “usual” baby items was challenging. Cotton nappies had to be hand-washed. She would go down to the Miljacka river near Dariva, and hand-wash the nappies in the water “Checking all time if shelling would start again, or if a sniper could see me.”

Today Sahida looks like Meliha- from the beginning of the story-, tall and proud, with a string of pearls and a pink coat. You could not imagine her walking the muddy Sarajevo by-roads and ducking under bombardment twenty years ago.

As in conflicts around the world, women step in to replace the men who have left their jobs in order to become soldiers. Some of them have to take up entirely new professions; some have to become versed in skills they are not qualified for. Sahida Kotur, a manual worker in the military factory PRETIS before the war, as the sole bread-winner in her family, started a new business during war. She learned how to knit, collected old sweaters from the neighbourhood, undid them and made new ones. She carried those in big bags on her back from one end of Sarajevo to the other, under shelling and bombardment, and traded those sweaters with the army for cigarettes. The cigarettes she traded for food and old sweaters. She insists on wearing slippers and shoes that hide her toes today. The shelling made her a refugee within her city; she fled her home and had nothing to wear. She was given shoes that were a size smaller, they deformed her feet and toes and she now insists on hiding them.

“Bombing and shelling stops, peace treaties are signed, but war means that we are for ever bombarded from inside”

Many women doctors worked without electricity and water, without adequate medical supplies and medication. Jasmina Gutic, an expert gynecologist and professor, remembers how they had to carry babies out of the hospital basement after delivery in order to be able to see if they were ok. The deliveries took place with the use of lamp oil and she said how all new-born babies had a little black nose from the camp oil. Professor and doctor Vanesa Beslagic, a radiologist, had to deliver diagnosis with equipment that could not be repaired, or even powered. The late doctor Nada Zjuzin, a university professor of physical therapy, said how she often, like many of her colleagues, stayed in the hospital for a number of days, because it was too dangerous to go home when bombardment or shelling started. Doctor Amela Kuskunovic, today a radiologist and politician, only rolls her eyes when I ask her about being a young doctor during the war. She worked at the emergency ward, and all of the injured were brought there first. I was there once and there was so much blood I thought they would never be able to clean it.

As a feminist I am ashamed to say I did not stand side-by-side with these intelligent, brave and beautiful Sarajevo women. I had been bombarded twice before and I did not know how to cope with it when it happened to my hometown but to flee after half a year. I was a young girl waking up to the sound of bombardment and to the sight of low-flying planes as my father tried to persuade me those were birds in the Baghdad skies in 1980. A few days later I would watch the anti-aircraft fire from the roof of our house and make my father promise a similar spectacle of fireworks for my wedding. In 1989, I had my first job when Iraqi earth-to-earth missiles hit Tehran and I had to flee to the surrounding mountains. In Sarajevo I ended having panic attacks during shelling, I would suffocate in my own fear.

I never had fireworks for my wedding, and still find it difficult to be near them. An anecdote was recorded by my fellow classmates in England, after I had fled from the bombardments of Sarajevo, during the Guy Fawkes’ fireworks. It was my first month in England, I was in my student room, and I heard outgoing shelling. Then I heard incoming and anti-aircraft fire. I was so upset that war had started in England, too, that I started packing my bags in order to return to Sarajevo. I thought, “If I have to be in a war, then I will be at home.” I was on the staircase with my suitcase when other students found me and explained that it was not a war but fireworks.

1. Klix.ba Interview with Meliha Varesanovic, consultada el 27-12-2015.

Photography: © Milomir Kovačević Strašni

© Generalitat de Catalunya