Political conflict damages relationships between individuals and communities, as well as trust in public institutions and the state. Building peace therefore requires attention to relationships. In its simplest form, reconciliation is the process of addressing conflictual and fractured relationships after political conflict. The term reconciliation can, however, be confusing when applied to societies emerging from violent conflict, as it requires not only the reconciling of broken relationships (as the term semantically implies), but also the process of building previously non-existent relationships between individuals, groups and institutions. This can include a range of activities at multiple levels from inter-personal and inter-group initiatives that could include positive encounter, dialogue, education and mutual understanding, to political level trust-building processes, including public acknowledgement and apologies of wrongdoing, institutional reform, truth recovery and reparations.

The process of rebuilding relationships is also a multi-directional process. To help understand this complexity, we have proposed a “working definition” of reconciliation that, we argue, involves five interwoven and related strands1:

1. Developing a shared vision of an interdependent and fair society. This requires the involvement of the whole society, at all levels. Although individuals may have different opinions or political beliefs, the articulation of a common vision of an interdependent, just, equitable, open, and diverse society is a critical part of any reconciliation process.

2. Acknowledging and dealing with the past. The truth of the past, with all its pain, suffering, and losses, must be acknowledged, and mechanisms implemented providing for justice, healing, restitution or reparations, and restoration (including apologies, if needed, and steps aimed at redress). To build reconciliation, individuals and institutions need to acknowledge their own role in the conflicts of the past, accepting and learning from it in a constructive way to ensure non-repetition.

3. Building positive relationships. Following violent conflict, relationships need to be built or renewed, addressing issues of trust, prejudice, and intolerance in the process. This results in accepting both commonalities and differences, and embracing and engaging with those who are different from us.

4. Significant cultural and attitudinal change. The culture of suspicion, fear, mistrust, and violence is broken down, and opportunities and space open up in which people can hear and be heard. A culture of respect for human rights and human differences is developed, creating a context for each citizen to become an active participant in society and feel a sense of belonging.

5. Substantial social, economic, and political change. The social, economic, and political structures that gave rise to conflict and estrangement are identified, reconstructed or addressed, and transformed. This strand can also be thought of as being about equality and/or attaining equity between groups.

Three additional points are important in understanding this definition.

First, paradoxes, tensions, and even contradictions are always present in reconciliation processes. For example, the articulation of a long-term, interdependent future (Strand 1) is often in tension with the requirements for justice (Strand 2)2. Fostering economic change (Strand 5) may also require a change in resource allocation or ownership (for example in post-Apartheid South Africa), yet may negatively affect the potential to build positive relations between those who gain and lose in this process of redistribution (Strand 3).

Reconciliation involves developing a shared vision of the future, dealing with the past, and building positive relationships with cultural and attitudinal change

Second, reconciliation is a morally loaded concept and an ideological term. Relationships are fundamental to human interaction and, as a result, reconciliation is often linked to our basic beliefs about the world3. Someone from a theological background might stress the importance to building empathy within the reconciliation process, while a human rights advocate might wish to promote the rule of law as an effective means of regulating how people engage with one another and to wider institutions.

Third, reconciliation is not just about individual outcomes in isolation (say, addressing social inequalities between groups, Strand 5) but rather the process of addressing the detail of the five strands holistically. This is challenging because the social, interpersonal, and political contexts are in constant flux. Reconciliation should, therefore, be understood as dynamic and progressive, but also conflictual and prone to setback. As such, reconciliation should be measured as the ability of a society to manage the complex paradoxes and tensions inherent within, and between, the five strands, as outlined above.

We cannot simply apply our working definition to any context without reflection and analysis. Each context is unique, and even the language used (including the term reconciliation itself), can be fraught with controversy and sensitivity. In some societies reconciliation is seen as a ‘soft’ term that favours compromise over formal justice (this is often heard in Latin American countries), and has been rejected by some victims and human rights advocates. In others societies, such as Northern Ireland, the connotations are different. In our research in this region, we found apprehension to using the term reconciliation among some peace-focused practitioners, not because it is seen as ‘soft’ but rather because it is understood as a process that fundamentally transforms societal and political relations4. They have indicated to us that they have experienced resistance from some when initiatives explicitly use the term reconciliation as it implies a ‘hard’ process that requires meaningful, but potentially uncomfortable personal, cultural or community change.

Paradoxes, tensions, and even contradictions are always present in reconciliation processes

At the political level in Northern Ireland a more minimalist view of reconciliation has been adopted, which accepts that different communities (with different political aspirations) exist, but only limited efforts have been made to break down the social, residential and educational segregation which exists between the two main communities. With significant improvement in the security context since the 1998 Agreement, and trust between estranged groups generally better than in the past, attitudes towards ‘the other’ have gradually improved5, but the underlying divisions remain unresolved. Trust between political parties has deteriorated significantly in recent years and at the time of writing this article the devolved legislative Assembly (at the core of the 1998 Agreement) has been suspended for over a year.

Our research shows that this political impasse has also been exacerbated by the lack of a common vision of the future of the region (Strand 1). The 1998 Agreement provided for the establishment of a devolved local government structure within the United Kingdom: a compromise for unionists who wish to remain within the UK at large, and, for nationalists and republicans, a stage in a longer-term process towards a constitutionally united (Northern Ireland joining the Republic of Ireland) island of Ireland. This has resulted in different political understanding of what a ‘reconciled’ society might ultimately look like. At the risk of generalising, for republicans the desired future is of equal and respectful relationships between communities in a united Ireland (they use the term reconciliation to capture this). For unionists, it is a limited form of ‘sharing’ power with nationalists within a devolved and political body, still dominated by British institutions and culture (they generally avoid the term reconciliation).

As a short-term goal following prolonged violent conflict, a minimalist approach that promotes tolerance of ‘the other’ might be a useful first step. However, without creating conducive or supportive conditions for inter-community interventions to thrive and sustainable relationships to develop, the danger of getting stuck at this stage or backsliding is ever-present.

Reconciliation should be measured as the ability of a society to manage the complex paradoxes and tensions inherent within

Our research has found that there is a b public desire for the political classes to jointly design – and publicly commit – to a process of horizontal and vertical relationship building. While community-focused relationship-building work has been financially well supported (for example, the EU alone has contributed nearly €2 billion for community-based work) and well-received with the general population, without significant policy-making to systemically address inter-communal division, its impact is somewhat limited.

Reconciliation is a challenging and even paradoxical concept that is highly contextual. In any setting, a genuine interrogation of how a society understands the core elements of reconciliation is vital. This may uncover differences between those who view reconciliation as a transformative process (were underlying differences are addressed, new relationships and cultures of connection emerge and all concerned change in the process) and those who view it as a more limited, functional process (basic levels of respect and tolerance but with little social interaction or addressing root causes of the conflict). In doing so, we might more readily address these inconsistencies from the outset of a peace process, ensure greater clarity and tailor approaches to both assuage genuine fears but also reward those willing to take greater risks for sustainable peace.

We have found our “working definition” to be a useful tool to “diagnose” the development of reconciliation processes over time and where new impetus might be required. In Northern Ireland, we would argue that greater efforts to find a common vision for the future, while also seizing the opportunity to address the hurts of the past, is now urgently required. In other societies, this emphasis might look quite different. What is important is that we remain attuned to the potential outcomes of choosing transformative or minimalist approaches to addressing a legacy of political conflict and monitor the outcomes these approaches deliver.

1. See among many other publications Hamber, B., & Kelly, G. (2009). Too Deep, too Threatening: Understandings of reconciliation in Northern Ireland. In H. van der Merwe, V. Baxter, & A. Chapman (Eds.), Assessing the Impact of Transitional Justice: Challenges for Empirical Research (pp. 265-293). Washington: United States Institute for Peace.

2. See Lederach, J. P. (1997). Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies. Washington D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press.

3. See van der Merwe, H. (2000). National and Community Reconciliation: Competing Agendas in the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In N. Biggar (Ed.), Burying the Past: Making Peace and Doing Justice after Civil Conflict. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

4. Hamber, B. and Kelly, G. (2017). Challenging the Conventional: Can Post-Violence Reconciliation Succeed? A Northern Ireland Case Study. Kofi Annan Foundation & Interpeace: New York.

5. Morrow, D., Robinson, G., & Dowds, L. (2013). The Long View of Community Relations in Northern Ireland: 1989-2012. ARK: Belf

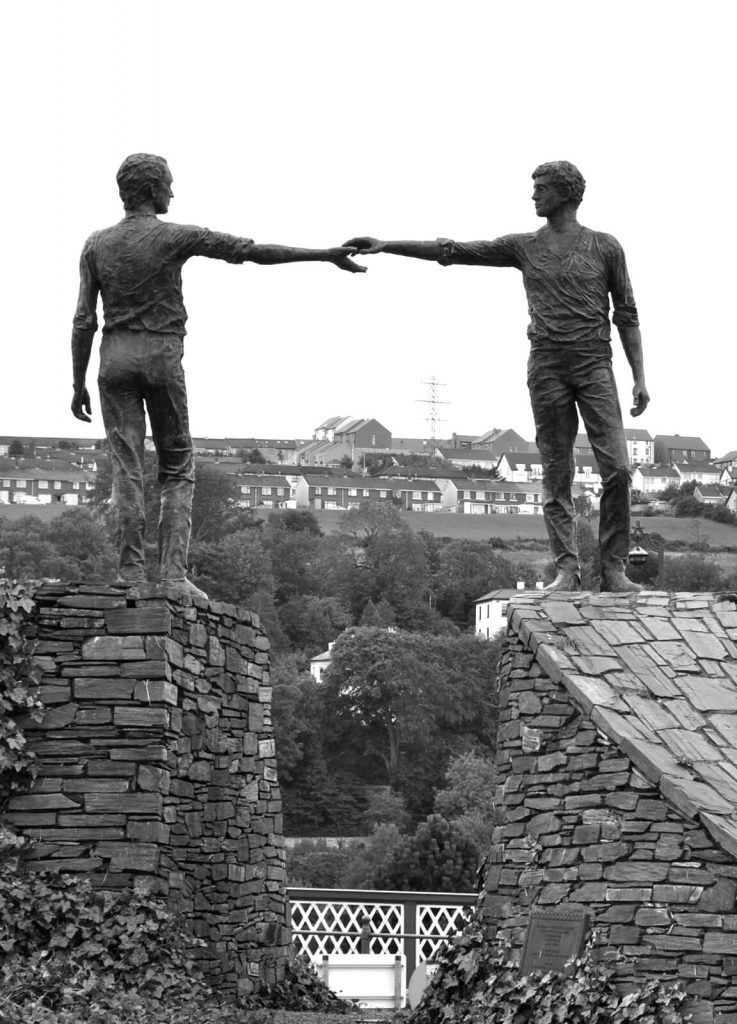

Photography : Hands Across the Divide. Monument in Derry (Londonderry)

© Generalitat de Catalunya