The assertion made several years ago by the Independent International Commission on Kosovo that understanding any conflict of which ethnicity is a part demands that language be given special attention (Mac Giolla Chríost, 2003: 1) remains as true to-day as it ever was. Language is implicated in all ethno-political conflicts and the case of the Irish language in the historical conflict in Northern Ireland is an effective illustration of how this applies.

While there has been political agreement in the region since 1998, and the erstwhile political enemies Sinn Féin and the Democratic Unionist Party are now sharing power in the Northern Ireland Assembly, the Irish language remains a complex and, at times, divisive issue. Irish is often described as being at the heart of a culture war in the region.

When the violent political conflict that is variously known as ‘the Troubles’ (the usual terminology of most journalistic commentators) or ‘the Long War’ (a phrase of Irish republican origin) started in the late 1960s no reasonable person could have foreseen the role the Irish language would come to play in that conflict. After all, it was widely assumed that the last native speakers of the tongue in Northern Ireland passed away sometime during the 1960s (Mac Giolla Chríost, 2005: 136).

The relationship between the language and the Long War begins in the prison known as HMP Long Kesh. During the period 1972-1976 hundreds of young men were interned there without trial on suspicion of being radical Irish republicans, and therefore implicated in the political violence which had already seen car bombs, assassinations and extensive street violence. They were held as prisoners with special Category Status, which meant that that were able to wear their own clothes, freely associate, not do prison work, receive food and other parcels from a regular stream of visitors, and to organize themselves as members of paramilitary organisations.

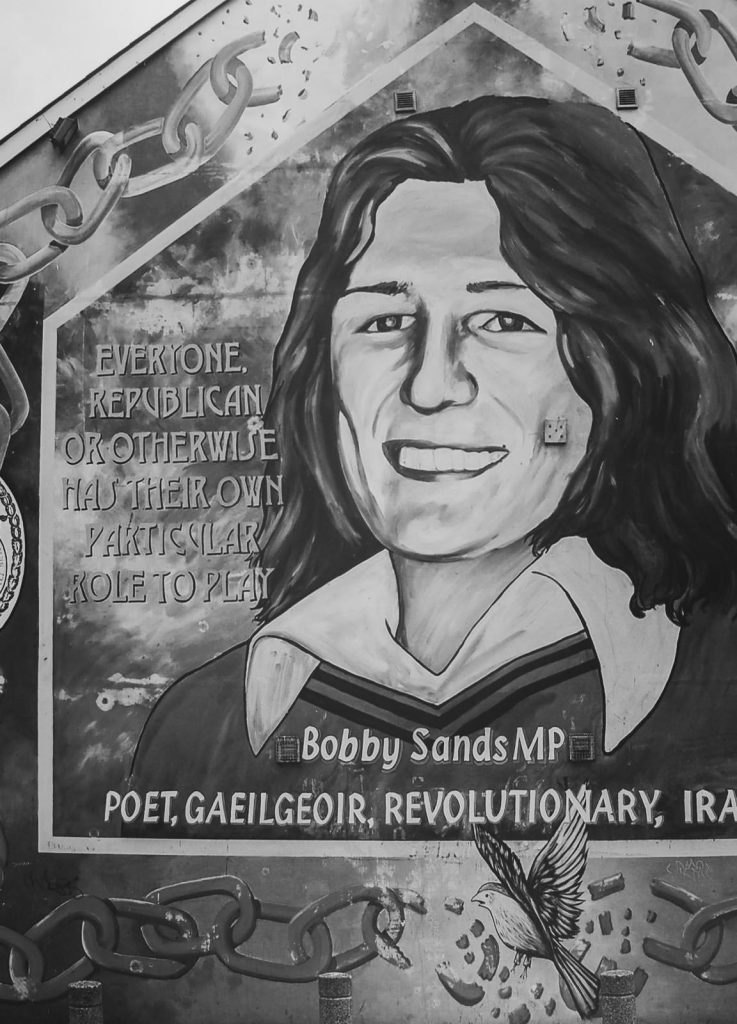

Under this regime some of the prisoners set about learning the Irish language. For some Irish republican prisoners this was part of a tradition that began at Frongoch internment camp in Wales in 1916 and continued at the Curragh internment camp in Ireland during the 1940s. Foremost among the young turks at HMP Long Kesh was Bobby Sands, who would later lead the fatal hunger strikes of 1981. Sands and like-minded colleagues learned their Irish under the guidance of a few of the older heads who had acquired some grasp of the language from their schooldays and at evening classes. As their numbers grew they soon organized themselves into so-called ‘Gaelic’ or ‘Gaeltacht’ huts.

The prisoners resisted the imposition of the new regime and the Irish language became a central feature of that resistance

This much is not particularly remarkable, but events took a dramatic and fateful turn in 1976. In March of that year the British Government decided to dispose of Special Category Status and also to replace the dormitory and communal style huts of HMP Long Kesh, known by the prisoners as the Cages, with cellular accommodation laid out in a distinctive H shape and designed to enable the isolation of the prisoners and to stymie their coherence as an incarcerated political community. As the new architecture replaced the old so HMP Long Kesh was re-named HMP the Maze.

Of course, the prisoners resisted the imposition of the new regime and the Irish language became a central feature of that resistance. Between 1976 and 1981 they embarked on an escalating series of protests that culminated in the hunger strikes of 1981, 10 of which ended with the death of the hunger striker. The first to die was Bobby Sands.

During this period the prisoners used the language as, in their own words, a weapon of resistance (Mac Giolla Chríost, 2012). They would use their own peculiar prison argot form of Irish, for which they coined the name ‘Jailic’ (an obvious play on ‘Gaelic’), for communication with each other as a type of code the prison guards could not understand. As the prisoners were held in their cells for 23 hours per day and could not freely associate, they also used the Irish lessons, shouted from cell to cell, in order to maintain their sense of togetherness, thereby sustaining their morale and psychological well-being.

During this period too the protesting prisoners were denied access to educational materials and so they resorted to having Irish language teaching and learning material smuggled in to them. Such was their determination an Irish-speaking core of prisoners quickly coalesced. The prisoners coined the term ‘Jailtacht’ for this linguistic community (a play on the word ‘Gaeltacht’).

The 10 deaths in 1981 led to a lull in Irish language activities amongst the prisoners for a number of years. But in the meantime their politicized adoption of the language was taken up by others beyond the prison. Sinn Féin was beginning to emerge as a political party of substance and the Irish language was a part of their mission. The cultural struggle came to be seen as a proxy, for some, of the armed struggle. Thus, the revival of Irish as a community language in places such as west Belfast was in part, at least, inspired by the Irish-speaking community that had somehow willed itself into existence inside HMP the Maze.

As they in turn were released as a part of the agreement so they too fed into the continued revival of the language in Northern Ireland more widely

Interest in the language in HMP the Maze was renewed towards the end of the 1980s as Séanna Walsh, one of Bobby Sands’ closest colleagues, was returned to jail by the courts in order to serve another long sentence. This time the prisoners set about learning the language in a much more structured fashion. As they were no longer protesting they had the freedom to do so. Hence, they developed their own intensive course and re-instituted the sense of an Irish-speaking community by establishing specifically designated Gaeltacht wings in the H-blocks.

By the time of the political agreement of 1998 a new cohort of Irish-speaking Irish republican prisoners had emerged. As they in turn were released as a part of the agreement so they too fed into the continued revival of the language in Northern Ireland more widely.

As a more usual form of democratic politics has sought to take root in the region it has proven difficult to disentangle the language from the historical politics of the Long War. Irish language activists have campaigned, to no avail, for an Irish Language Act in Northern Ireland. But such institutionalization of the language can only occur when Irish is regarded as a public good (Rawls, 1971) by society in general. In that regard much more work of engagement, explanation and persuasion remains to be conceived of and also to be undertaken.

Mac Giolla Chríost, D. (2003) Language, Identity and Conflict London: Routledge.

Mac Giolla Chríost, D. (2005) The Irish Language in Ireland from Goídel to Globalisation Londres: Routledge.

Rawls, J. (1971) A Theory of Justice Cambridge, MA: Belknap press of Harvard University Press.

Acronyms and glossary

Gaelic – an alternative term for the Irish language

Gaeltacht – an Irish-speaking community

HMP – Her Majesty’s Prison

Photography : Marcella / CC BY / Desaturated. – Mural painting of Bobby Sands in Belfast –

© Generalitat de Catalunya